INFLECTION

INFLECTED LANGUAGES

21. Latin is an inflected language.

Inflection is a change made in the form of a word to show its grammatical relations.

a. Inflectional changes sometimes take place in the body of a word, or at the beginning, but oftener in its termination.

vōx a voice

vōcis of a voice

Vocō. I call.

Vocat. He calls.

Vocet. Let him call.

Vocāvit. He has called.

Tangit. He touches.

Tetigit. He touched.

b. Terminations of inflection originally had independent meanings which are now obscured. They correspond nearly to the use of prepositions, auxiliaries, and personal pronouns in English. Thus, in vocat, the termination is equivalent to he or she; in vōcis, to the preposition of; and in vocet the change of vowel signifies a change of mood.

c. Inflectional changes in the body of a verb usually denote relations of tense or mood, and often correspond to the use of auxiliary verbs in English.

Frangit. He breaks. (is breaking)

Frēgit. He broke. (has broken)

Mordet. He bites.

Momordit. He bit.1

22. The inflection of Nouns, Adjectives, Pronouns, and Participles to denote gender, number, and case is called Declension, and these parts of speech are said to be declined.

The inflection of Verbs to denote

voice, mood, tense, number, and person is called Conjugation, and the verb is said to be conjugated.

Note— Adjectives are often said to have inflections of comparison. These are, however, properly stem-formations made by derivation (§ 124, footnote).

23. Adverbs, Prepositions, Conjunctions, and Interjections are not inflected and are called Particles.

Note— The term Particle is sometimes limited to such words as num, -ne, an (interrogative), nōn, nē (negative), sī (conditional), etc., which are used simply to indicate the form or construction of a sentence.Footnotes

ROOTS, STEMS AND BASES

24. The body of a word, to which the terminations are attached, is called the stem. The stem contains the idea of the word without relations; but, except in the first part of a compound (as, arti-fex, artificer), it cannot ordinarily be used without some termination to express them.1

Thus the stem vōc- denotes voice; with -s added it becomes vōx (a voice or the voice) as the subject or agent of an action; with -is it becomes vōcis, and signifies of a voice.

Note— The stem is in many forms so united with the termination that a comparison with other forms is necessary to determine it.

25. A root is the simplest form attainable by separating a word into its component parts. Such a form contains the main idea of the word in a very general sense, and is common also to other words either in the same language or in kindred languages.2

Thus the root of the stem vōc- is VOC, which does not mean to call, or I call, or calling, but merely expresses vaguely the idea of calling, and cannot be used as a part of speech without terminations. With ā- it becomes vocā-, the stem of vocāre (to call); with āv- it is the stem of vocāvit (he called); with āto- it becomes the stem of vocātus (called); with -ātiōn- it becomes the stem of vocātiōnis (of a calling). With its vowel lengthened it becomes the stem of vōx, vōc-is (a voice: that by which we call). This stem vōc-, with -ālis added, means belonging to a voice; with -ŭla, a little voice.

Note— In inflected languages, words are built up from roots, which at a very early time were used alone to express ideas, as is now done in Chinese. Roots are modified into stems, which, by inflection, become fully formed words. The process by which roots are modified, in the various forms of derivatives and compounds, is called stem building. The whole of this process is originally one of composition, by which significant endings are added one after another to forms capable of pronunciation and conveying a meaning. Roots had long ceased to be recognized as such before Latin existed as a separate language. Consequently the forms which we assume as Latin roots never really existed in Latin, but are the representatives of forms used earlier.

26. The Stem may be the same as the root: duc-is (of a leader), fer-t (he bears); but it is more frequently formed from the root—

- By changing or lengthening its vowel.

scob-s (sawdust; SCAB, shave)

rēg-is (of a king; REG, direct)

vōc-is (of a voice; VOC, call). - By the addition of a simple suffix (originally another root).

fugā-, stem of fuga (flight; FUG + ā-)

regi-s (you rule REG + stem ending e/o-)

sini-t (he allows SI + ne/o-).3 - By two or more of these methods.

dūci-t (he leads; DUC + stem-ending e/o-)

- By derivation and composition, following the laws of development peculiar to the language. (See §§ 227 ff.)

27. The base is that part of a word which is unchanged in inflection:

serv- in servus

mēns- in mēnsa

īgn- in īgnis

a. The Base and the Stem are often identical, as in many consonant stems of nouns (as, rēg- in rēg-is). If, however, the stem ends in a vowel, the latter does not appear in the base, but is variously combined with the inflectional termination. Thus the stem of servus is servo-; that of mēnsa, mēnsā-; that of īgnis, īgni-.

28. Inflectional terminations are variously modified by combination with the final vowel or consonant of the Stem, and thus the various forms of Declension and Conjugation (see § 36 , § 164) developed.

Footnotes

2. For example, the root STA is found in the Sanskrit tishthami, Greek ἵστημι, Latin sistere and stāre, German fteben, and English stand.

3. These suffixes are Indo-European stem-endings.

GENDER

29. There are three Genders in Latin: Masculine, Feminine, and Neuter.

30. The gender of Latin nouns is either natural or grammatical.

a. Natural Gender denotes the sex of an object.

puer (m.) boy

puella (f.) girl

rēx (m.) king

rēgīna (f.) queen

Note 1— Many nouns have both a masculine and a feminine form to distinguish sex.

cervus, cerva stag, doe

cliēns, clienta client

victor, victrīx conqueror

Many designations of persons (as nauta sailor) usually, though not necessarily, male are always treated as masculine. Similarly names of tribes and peoples are masculine.

Rōmānī the Romans

Persae the Persians

Note 2— A few neuter nouns are used to designate persons as belonging to a class.

mancipium tuum your slave (your chattel)

Many pet names of girls and boys are neuter in form.

Paegnium, Glycerium

Note 3— Names of classes or collections of persons may be of any gender.

exercitus (m.), aciēs (f.), and

agmen (n.) army

operae (f. plur.) workmen

cōpiae (f. plur.) troops

senātus (m.) senate

cohors (f.) cohort

concilium (n.) council

b. Grammatical Gender is a formal distinction as to sex where no actual sex exists in the object. It is shown by the form of the adjective joined with the noun.

lapis māgnus (m.) a great stone

manus mea (f.) my hand

RULES OF GENDER

31. Names of Male beings, and of Rivers, Winds, Months, and Mountains, are masculine:

pater father

Iūlius Julius

Tiberis the Tiber

auster south wind

Iānuārius January

Apennīnus the Apennines

Note— Names of Months are properly adjectives, the masculine noun mēnsis, month, being understood: Iānuārius, January.

a. A few names of Rivers ending in -a (as, Allia), with the Greek names Lēthē and Styx, are feminine; others are variable or uncertain.

b. Some names of Mountains are feminine or neuter, taking the gender of their termination.

Alpēs (f.) the Alps

Sōracte (n.)

32. Names of Female beings, of Cities, Countries, Plants, Trees, and Gems, of many Animals (especially Birds), and of most abstract Qualities, are feminine.

māter mother

Iūlia Julia

Rōma Rome

Ītalia Italy

rosa rose

pīnus pine

sapphīrus sapphire

anas duck

vēritās truth

a. Some names of Towns and Countries are masculine or neuter.

Sulmō (m.)

Gabiī (m. plural)

Tarentum, Illyricum (n.)

b. A few names of Plants and Gems follow the gender of their termination.

centaurēum (n.) centaury

acanthus (m.) bearsfoot

opalus (m.) opal

Note— The gender of most of the above may also be recognized by the terminations, according to the rules given under the several declensions. The names of Roman women were usually feminine adjectives denoting their gēns or house (see § 108.b).

33. Indeclinable nouns, infinitives, terms or phrases used as nouns, and words quoted merely for their form, are neuter.

fās right

nihil nothing

gummī gum

scīre tuum

your knowledge (to know)

trīste valē a sad farewell

hōc ipsum diū this very “long”

34. Many nouns may be either masculine or feminine, according to the sex of the object. These are said to be of Common Gender.

exsul exile

bōs ox or cow

parēns parent

Note— Several names of animals have a grammatical gender, independent of sex. These are called epicene. Thus lepus (hare) is always masculine, and vulpēs (fox) is always feminine.

NUMBER AND CASE

35. Nouns, Pronouns, Adjectives, and Participles are declined in two Numbers (singular and plural) and in six Cases (Nominative, Genitive, Dative, Accusative, Ablative, Vocative).

a. The Nominative is the case of the subject of a sentence.

b. The Genitive may generally be translated by the English possessive, or by the objective with the preposition of.

c. The Dative is the case of the indirect object (§ 274). It may usually be translated by the objective with the preposition to or for.

d. The Accusative is the case of the direct object of a verb (§ 274). It is used also with many of the prepositions.

e. The Ablative may usually be translated by the objective with from, by, with, in, or at. It is often used with prepositions.

f. The Vocative is the case of direct address.

g. All the cases, except the nominative and vocative, are used as object cases; and are sometimes called oblique cases (cāsūs oblīquī)

h. In names of towns and a few other words appear traces of another case (the Locative), denoting the place where:

Rōmae at Rome

rūrī in the country

Note— Still another case, the Instrumental, appears in a few adverbs (§ 215.4).

RULES OF NOUN DECLENSION

36. Declension is produced by adding terminations originally significant to different forms of stems, vowel or consonant. The various phonetic corruptions in the language have given rise to the several declensions. Most of the case endings, as given in Latin, contain also the final letter of the stem.

Adjectives are, in general, declined like nouns, and are etymologically to be classed with them; but they have several peculiarities of inflection (see § 109 ff.).

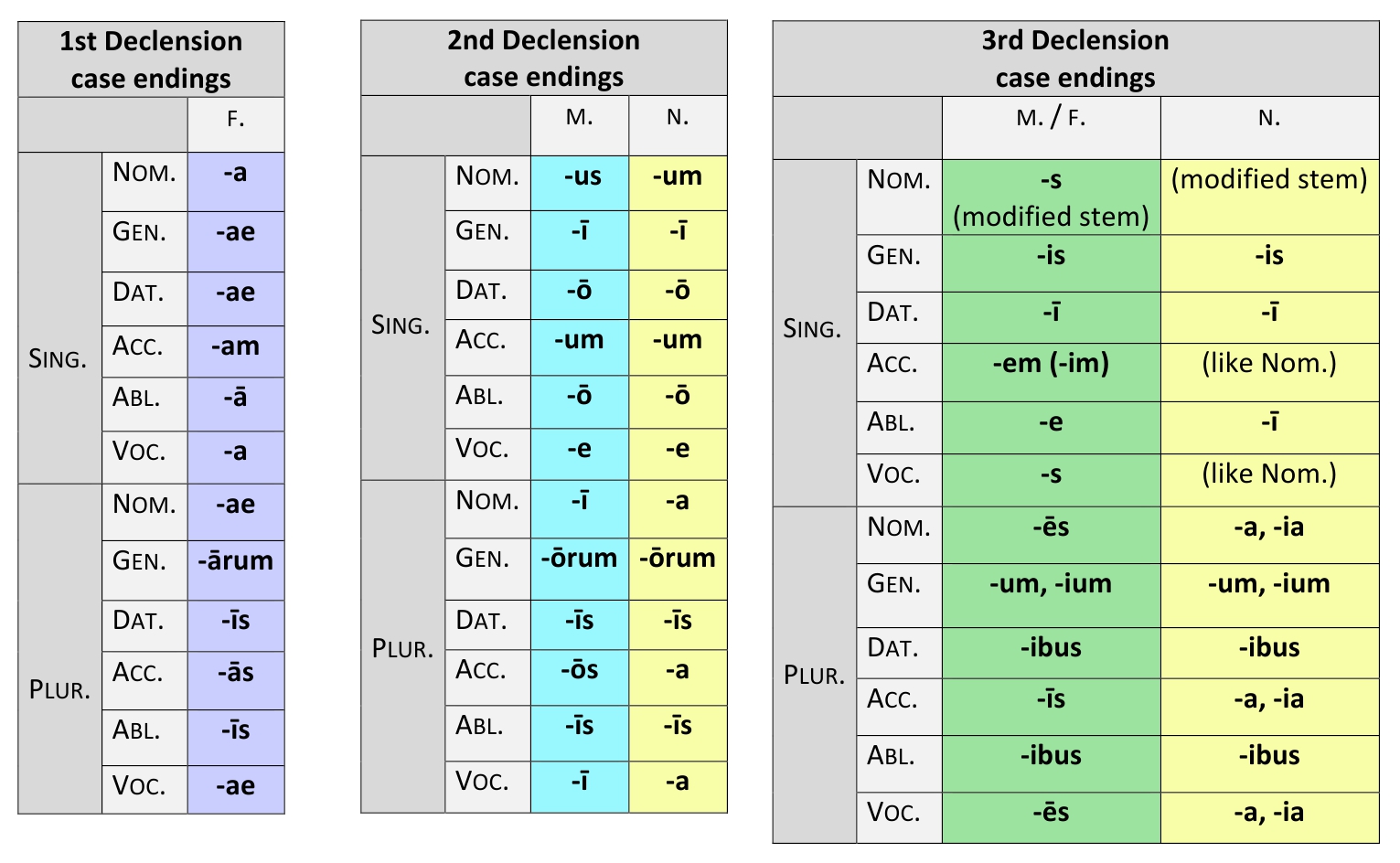

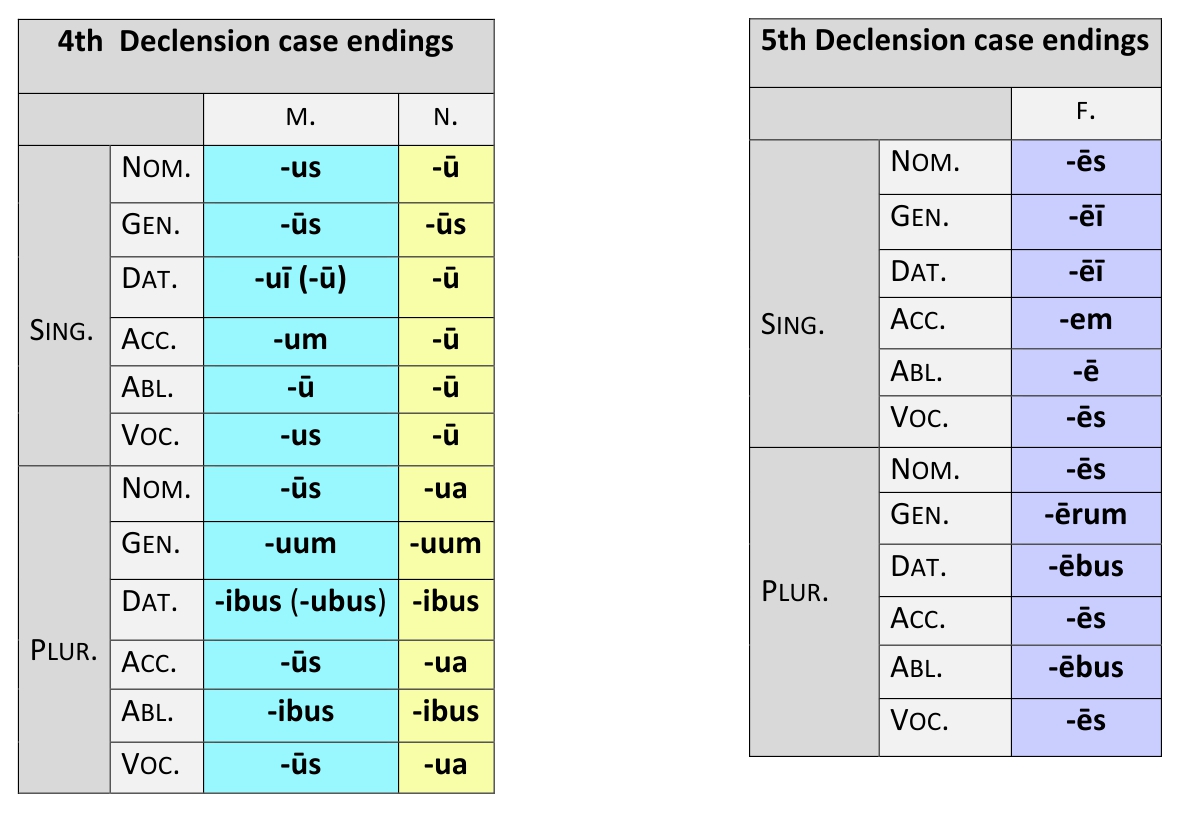

37. Nouns are inflected in five Declensions, distinguished by the final letter (characteristic) of the Stem, and by the case-ending of the Genitive Singular.

| Declension | Characteristic | Genitive Singular |

| 1st | ā | ae |

| 2nd | ŏ | ī |

| 3rd | ĭ or consonant | ĭs |

| 4th | ŭ | ūs |

| 5th | ē | ēī |

a. The Stem of a noun may be found, if a consonant stem, by omitting the case ending; if a vowel stem, by substituting for the case ending the characteristic vowel.

38. The following are General Rules of Declension:

a. The Vocative is always the same as the Nominative, except in the singular of nouns and adjectives of the 2nd declension ending in -us, which have -e in the Vocative.

b. In neuters the Nominative and Accusative are always alike, and end in -ă in the plural.

c. The Accusative singular of all masculines and feminines ends in -m; the Accusative plural ends in -s.

d. In the last three declensions (and in a few cases in the others) the Dative singular ends in -ī.

e. The Dative and Ablative plural are always alike.

f. The Genitive plural always ends in -um.

g. Final -i, -o, and -u of inflection are always long; final -a is short, except in the Ablative singular of the 1st declension; final -e is long in the 1st and 5th declensions, short in the 2nd and 3rd. Final -is and -us are long in plural cases.

CASE ENDINGS OF THE FIVE DECLENSIONS

39. The regular case endings of the five declensions are as follows.1